The Fort Carillon or Ticonderoga

For English version, please click on the flag

This chapter has been based on the Wikipedia site written on the Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga is a large XVIIIth century fort built at a strategically important narrows in Lake Champlain where a short

traverse gives access to the north end of Lake George in the state of New York, USA.

Strategic place of the Fort Carillon

The fort controlled both commonly

used trade routes between the English-controlled Hudson River Valley and the French-controlled Saint Lawrence River Valley.

The name "Ticonderoga" comes from an Iroquois word tekontaró : ken, meaning "it is at the junction of two waterways".

Fort Ticonderoga was the site of four battles over the course of twenty years.

Strategical place of the Fort

In 1755, the French began construction of Fort Carillon. The name "Carillon" came from the name of a former French officer

Pierre de Carrion, who established a trading post at the site in the late XVIIth century. Construction

proceeded on the fort slowly through 1756 and 1757. The fort's primary goal was to control the south end of Lake Champlain,

and to prevent the British to enter the Vermont region which was as that time a French territory.

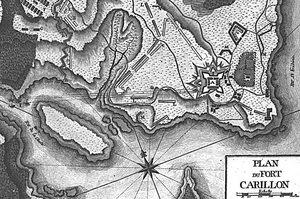

Map of the Fort Carillon

The Fort seen from the lake Champlain

In 1757 the French launched a very successful attack upon Fort William Henry from the nearly complete Fort Carillon.

On July 8, 1758 the British, under General James Abercrombie, staged a frontal attack against hastily assembled

works outside the fort's main walls (which were still under construction) in the Battle of Carillon. Abercrombie

tried to move rapidly against the few French defenders, opting to forgo field cannon, he relied upon his 16,000 troops. The

British were soundly defeated by 4,000 French defenders. This battle gave the fort a reputation for invulnerability,

although the fort never again repulsed an attack. The 42nd Regiment of Foot (the Black Watch) was especially badly

mauled in the attack on Fort Carillon, giving rise to a legend involving the Scottish Major Duncan Campbell.

The terrifying reputation of the Native Americans, for the most part allied to the French, is thought to have

provoked the wave of panic that apparently overtook British troops retreating in great disorder by day's end.

French patrols later found equipment strewn about, boots left stuck in mud, and many wounded on their stretchers left

to die in clearings. In fact, few Natives were actually present during the battle, a large contingent of them having

been sent by French governor Vaudreuil on a useless mission to Corlar. The misdirection of Indian fighters gave

Montcalm all the more reason to pester at his rival Vaudreuil, complaining that his actions had cost them the

opportunity to completely destroy the retreating British (who would later regroup south of Lake George).

The Battle of Carillon (1758)

The fort was captured the following year by the British, under General Jeffrey Amherst, in the Battle of Ticonderoga.

No longer considered a "front line" fortification, Ticonderoga was not well-maintained by the Crown and manned by a

token force. On May 10, 1775, the British garrison of twenty two soldiers was surprised by a small force of Vermonters who

called themselves the Green Mountain Boys, and were led by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold, who entered the fort

through a breach in the wall. Allen later claimed that he demanded to the British commandant that he surrender the

fort "In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!"; however, his surrender demand was made to a

junior officer, not the commandant, and no other witnesses remembered Allen uttering such a phrase.[4] Not a single

shot was fired. The colonies obtained a large supply of cannons and powder, much of which was hauled 300 km by Henry

Knox during the winter of 1775-1776, to Boston, to support the Siege of Boston. The fort itself was marginally

defensible, but at least provided shelter and an excellent view of the surrounding waterways.

In 1775, the British returned from Canada and moved down Lake Champlain under General Carleton. A ramshackle

fleet of American gunboats delayed the British until winter threatened (see: Battle of Valcour Island), but the

attack resumed the next year under General Burgoyne.

In 1777 the British forces moving south from Canada drove the Americans back into the fort, then hauled cannon

to the top of undefended Mount Defiance, which overlooked the fort.

Faced with bombardment, Arthur St. Clair ordered Ticonderoga abandoned on July 5, 1777. Burgoyne's troops

moved in the next day.

The colonials quickly withdrew across the Lake to Fort Independence on the Vermont side of the Lake. They

soon abandoned that fort as well and retreated south to Saratoga. Seth Warner, now the leader of Vermont

Republic's Green Mountain Boys, having conducted the American rear guard the previous year as the Americans

retreated from Quebec to Ticonderoga, showed his prowess and cool headedness by very nearly defeating the

pursuing British. The rear guard led by Americans Warner, Francis and Titcomb demonstrated significant

effectiveness in this defensive maneuver. Warner almost certainly would have defeated the larger British force

had it not been for the arrival of the flanking German troops sent by Burgoyne. This rear guard is known as

the skirmish at Hubbardton and ultimately allowed Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair to retreat to Saratoga with the

majority of the Ticonderoga force. This set up the ultimate defeat of Burgoyne later that year in Saratoga.

In total 67% of Warner's troops made it through the rear guard battle and effectively stopped the British pursuit.

The redition of General Burgoyne (1778)

After Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga, the fort at Ticonderoga became increasingly irrelevant. The British

abandoned Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point in 1780. Local farmers began stripping building materials, such

as dressed stone, from the old forts. Also, the climate in the area caused considerable freezing and thawing,

with resulting buckling of stone walls.

The fort is privately owned and was restored in 1909. It is maintained as a tourist attraction, opening for

the season on May 10th every year, closing in late October. Re-enactments of the French and Indian War period

are held annually.

Aerial view of the Fort

The fort was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960[1] Included in the landmarked area are three

land masses, including on promontory across Lake Champlain from the fort, in Vermont.[5]

Retour à la page principale.

Retour à la page principale.

.